The first month of the new year is almost over, and it’s time for the market anomaly of the month. Following the Santa Claus rally post, we now focus on the “January effect”: positive abnormal returns in January.

3 Reasons for the January Effect

First of all, what are the economic reasons for higher returns in January?

- Taxes: Investors aim at minimizing their tax bills. Hence, they realize losses on investments before the end of the year, and sell off poorly performing investments. Reinvesting the resulting cash funds pushes up prices in January.

- Window dressing: Asset managers want to present a strong portfolio at the end of the year to their clients. Hence, they sell off poorly performing investments before the end of the year. Reinvesting these funds in January pushes up prices even further.

- Gifts: Money given as a Christmas gift is invested in January.

- Investor sentiment: People usually meet the new year with optimism. E.g., the Consumer Confidence Index is more likely to peak in January than in other months. This optimism drives up stock market participation.

January Effect Around the World

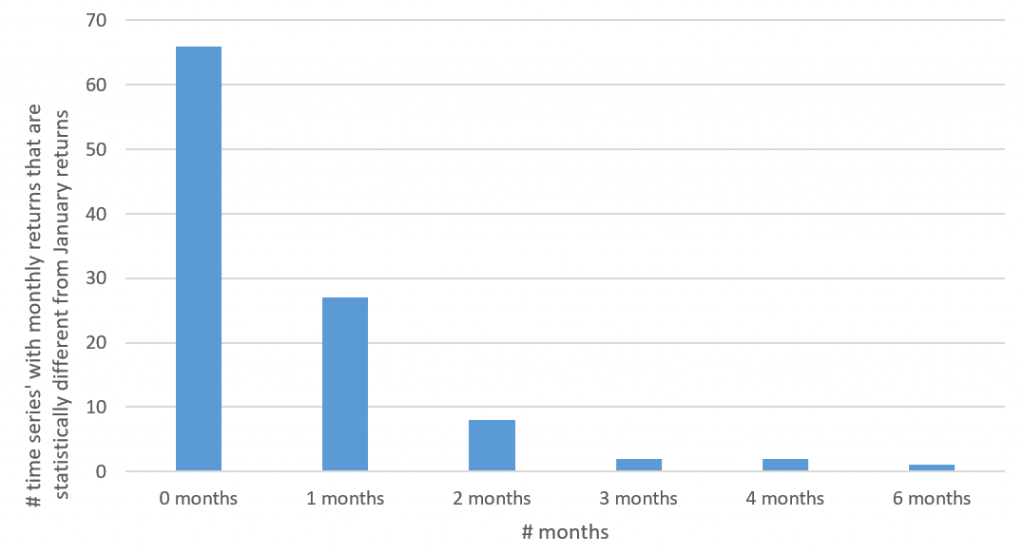

According to most accounts, Sidney Wachtel first provided empirical evidence for the January effect im 1942 for US American stocks. Since then, many researchers have replicated the analysis with mixed results. To see whether the effect is still prevalent, Gerardo Perez revisited the question in his 2017 International Journal of Financial Research paper “Does the January Effect Still Exists?”. He analyzes monthly returns of 106 stock market indices from 86 countries. Figure 1 shows how many monthly time series differ from the January return time series.

Overall, there is little evidence for a January effect. For 66 indices, January returns and returns in other months do not differ significantly. 27 (13) indices have one month (two or more months) with a statistically significantly different monthly return than in January. Similarly, a Kruskal-Wallis test indicates that returns for all months of the year come from the same distribution for 86% of the indices.

The Disappearing Effect

Interestingly, if only the last fifteen years are considered, returns of more than 93% of the indices come from the same distribution. Hence, the January effect seems to vanish over time. One explanation for this disappearence is that communication technology has increased informational efficiency. E.g., high-frequency trading may close pricing gaps more quickly and reduce opportunities for large abnormal returns.

Take-away: Don’t Put All Your Investments in One Month

Even though the January effect does not systematically prevail any more, some exceptions confirm the rule. E.g., DAX30 investors realized a 5.82% return in January 2019. So, stay tuned for more critical analyses of market anomalies to exploit!

You may also like