The financial crisis 2007/2008 again revealed that counterparty risk is front and center in financial markets. A consequence of counterparty risk: reliable market participants, with a low default probability, can require extra compensation for trading with riskier counterparties – at least in theory.

In a previous post, we had a look at the pricing effect of counterparty risk in the CDS market by the seminal paper of Arora et al. (2012). The main take-away: there is basically no impact – and Arora and coauthors argue that this is because of full collateralization.

Collateralization vs. counterparty choice

Today, we consider another explanation provided by Du, Gadgil, Gordy, and Vega in their 2015 paper “Counterparty Risk and Counterparty Choice in the Credit Default Swap Market”. The authors use a CDS transaction dataset provided by the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC). This dataset is extremely granular: The authors observe who trades with whom, on which underlying, at which date, at which spread.

Who are the CDS dealers?

Just like Arora et al. (2012), Du and coauthors do not find a significant pricing effect of counterparty risk. To tackle their main questions, they first run a logit model to identify the determinants of counterparty choice. The result is intuitive: more risky dealers (those with high CDS premia) act as a counterparty less often. Also, market participants are more likely to choose dealers with whom they recently traded. This result could be a sign that netting opportunities are part of the value of a business relationship. Assume that you recently purchased protection from a dealer. You now want to sell protection. Doing so with the same dealer allows you to net the two trades.

If dealers are safe, what does a CCP add?

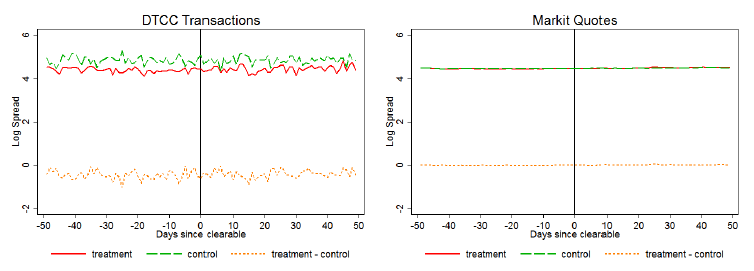

Finally, the authors analyze how spreads evolve around the time a CDS becomes eligible for central clearing. Figure 1 shows the average transaction spread (left panel) and average quoted spread (right panel) for clearing-eligible (red line) and clearing-ineligible (green line) CDS contracts as well as the difference between them (yellow line).

Figure 1: Average transaction price (left panel) and average price quote (right panel) of clearing eligible contracts (red line), clearing ineligible contracts (green line) around the date of central clearing. The yellow line shows the differences between the two groups. Source: Du et al. (2015).

You see that you see nothing – there is no clear up- or downward movement with the beginning of central clearing.

The formal evidence

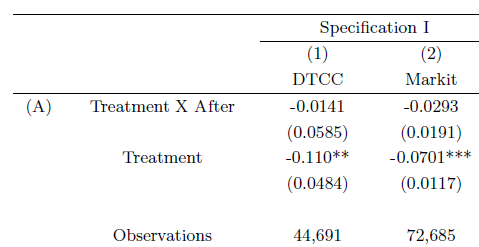

A formal comparison using a differences-in-differences approach in Table 1 confirms this visual impression. There is no significant effect of central clearing eligibility on transaction prices.

Table 1: Diff-in-diff analysis of the effect of central clearing eligibility on transaction spreads. Source: Du et al. (2015).

So, if market participants mitigate counterparty risk by choosing low-risk trade partners, this means two things.

- There are no pricing effects of counterparty risk.

- There is no effect of central clearing on transaction prices: Central counterparties (CCPs) are just another safe counterparty. They do not offer a unique option to trade with a low-risk counterparty.

Central clearing in CDS markets: Solution for a non-problem?

In a nutshell, the paper shows the importance of understanding market microstructure to ensure effective regulation: If investors only trade with safe counterparties anyway, mandatory central clearing does not reduce counterparty risk. However, there is a risk of higher transaction costs due to clearing fees and additional collateral requirements. These can cause a reduction in trading volume and market liquidity. In summary: a reform to increase market stability could in the end decrease market stability.

You may also like